ON THIS PAGE

- Introduction

- Cycles of Suffering

- Cycles of Healing and Happiness

- Healing Cycle: Seeking to Engage and Transform Suffering

- Healing and Happiness Cycle: Seeking True Goods

- Contemplative Practices for Seeking to Engage and Transform Suffering

- Contemplative Practices and Seeking True Goods

- Summary and Conclusions

- Exercises and Handouts

- Additional Notes

Introduction

Here I share a framework for understanding fundamental cycles of suffering and cycles of healing and happiness that all people experience, and how these cycles entail particular relationships among key brain circuitries.

I strongly recommend reading Key Brain Circuitries first, because it provides the foundation for what I share here.

By ‘cycle’ I mean a set of experiences and actions that unfold repeatedly, in the same order, and typically in a self-perpetuating way. This will become very clear below.

I introduce and explain this framework in three steps.

First, I will explain what I call ‘cycles of suffering,’ which involve relationships among key brain circuitries, and briefly illustrate them with examples.

Second, I explain and illustrate what I call ‘cycles of healing and happiness,’ and roles of the key brain circuitries in those cycles. This circuitries and cycles framework can be used to increase our understanding of all kinds of human suffering, including depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress, addictions and various problems with regulating emotions and impulses.

Third, I explain how the circuitries and cycles framework can be used to understand potential pathways to healing, including how therapy and contemplative practices can harness key brain circuitries to bring healing, freedom and happiness. I particularly focus on how the seeking, satisfaction and embodiment circuitries can be harnessed by contemplative practices – especially those that cultivate mindfulness, kindness, compassion and love – to transform suffering and bring genuine happiness.

Once familiar with the framework – especially when understanding is grounded in mindful attention to our moment-to-moment experience – we can see how the circuitries of fear, seeking, satisfaction and embodiment are major drivers of our thoughts, feelings and behaviors.

This includes insights into our habitual ways of attempting to regulate emotional and physiological states; insights into psychological symptoms with which we may struggle; insights into our values, hopes, and life goals; and insights into our moment-to-moment reactions to what is unpleasant or pleasant, feared or wanted, unsatisfying or fulfilling.

In short, this circuitries and cycles framework is offered as a set of clarifying conceptual tools for exploring experience and behavior, for understanding suffering and healing, and for choosing and getting the most from different types of therapy and from the contemplative practices of humanity’s great philosophical, religious and spiritual traditions.

Cycles of Suffering

Human beings are often caught in self-perpetuating cycles of suffering. We can understand these cycles, in part, as unhealthy relationships among the circuitries of fear, seeking, satisfaction and embodiment.

What makes cycles of suffering self-perpetuating? The brain’s seeking circuitry is focused on avoiding and escaping suffering in ways that do not really address one’s pain and problems (let alone bring genuine and lasting satisfaction or happiness), but instead keep them going or even make them worse.

What do you want to avoid? Which feelings? Which thoughts? Which memories?

Cycles of suffering are caused (and partly constituted by) seeking to avoid and escape suffering in ways that only perpetuate it. Cycles of suffering are often cycles of addiction, defined broadly to include all habitual behaviors used repeatedly to avoid and escape from suffering, including habitual mental behaviors like obsessing and ruminating.

All of these cycles of suffering – however addictive or harmful – are about the pursuit of quick fixes that bring no more satisfaction or ‘reward’ than this: brief and partial escape from an unwanted experience.

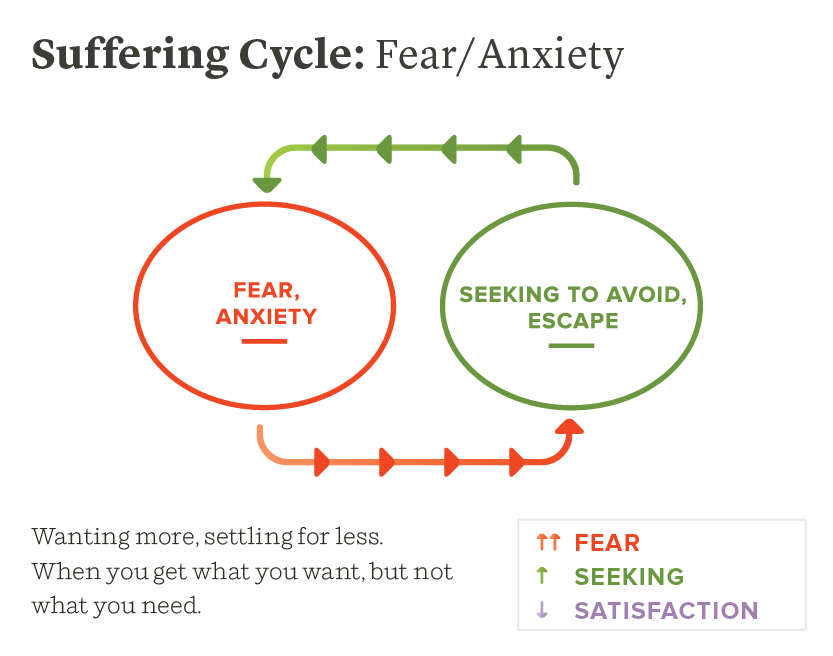

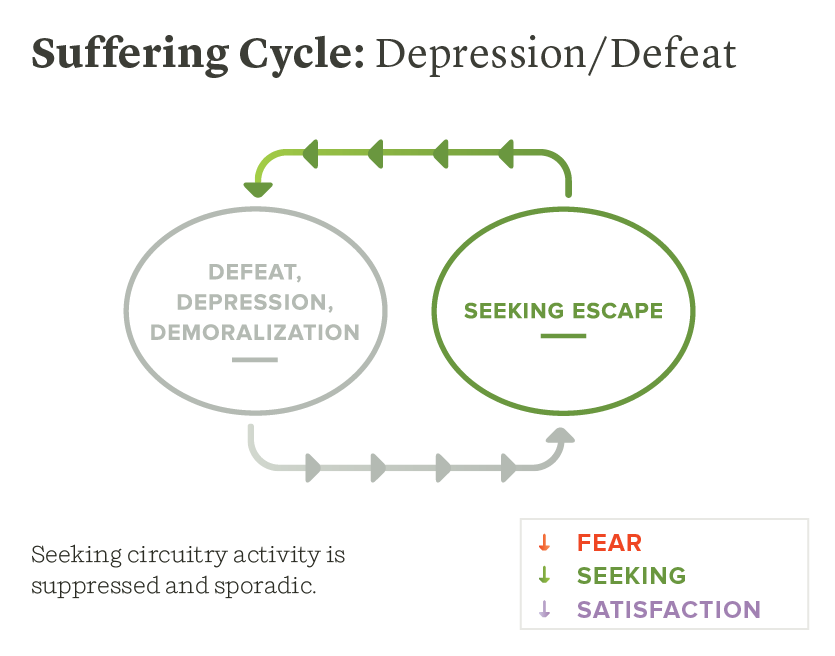

Different cycles of suffering involve distinct unhealthy relationships among the circuitries of fear, seeking, satisfaction and embodiment. And there are two very common cycles of suffering, one revolving around fear and anxiety, and the other around depression, defeat and demoralization.

These two common suffering cycles, and the corresponding activity of the brain circuitries of fear, seeking, satisfaction and embodiment, are described below.

Fear/Anxiety Cycle

In this suffering cycle seeking is focused on avoiding or escaping from things we are afraid of or anxious about, and/or on avoiding or escaping fear and anxiety. Thus the seeking circuitry is driven primarily by the fear circuitry, not by pursuit of what’s truly satisfying or fulfilling.

When the avoidance or escape end, the suffering from which we were seeking escape returns. And that suffering may be intensified, because the way we seek to avoid or escape may itself cause or increase our fear and anxiety (e.g., we may get drunk to avoid or escape fears and anxieties and then fear how our drunken behavior has affected loved ones and how they see us).

What are you actually seeking, in what you do every day? Quick-fix escapes? What brings lasting happiness? Your highest values and goals?

In this suffering cycle the embodiment circuitry is occupied with sensations of fear and anxiety, and with sensations of craving for escapes from sensations of fear, anxiety, and craving.

There’s little activation of the satisfaction circuitry anywhere in the cycle, with the possible exception of briefly while experiencing escape (e.g., intoxication, sexual pleasure, the brief ‘power high’ an angry outburst can give).

Depression/Defeat Cycle

In this cycle we feel stuck in and overwhelmed by something bad that’s already happened.

The fear circuitry is relatively inactive, since something that may have been feared has already come to pass.

The embodiment circuitry is occupied by sensations that go with feeling heavy, slow, tired, low-energy, bad about oneself, and unmoved by things that should be motivating or enjoyable.

The seeking circuitry is actually suppressed, so we don’t expect good things to happen or have much motivation for their pursuit. To the extent the seeking circuitry is active – whether sporadically in a burst like getting off the couch to go out and drink (or shop or have sex), or at an ongoing low level as in someone motivated to smoke cannabis and watch TV all day – it focuses on escaping the bad feelings and sensations of depression and defeat. (This is true even when we are avoiding embodied emotional experiences by ruminating on negative, pessimistic and/or self-denigrating thoughts, memories and fantasies.)

As with the fear/anxiety cycle, when the escape behavior ends the suffering of depression and defeat returns. Sometimes the depression and feelings of defeat are even worse than before, because the escape behavior (or the substance used, or the effects of withdrawing from the substance) itself causes depression and feelings of defeat.

And of course states of depression involve little or no activity of the satisfaction circuitry. There is no satisfaction, contentment or happiness in such states of suffering.

Finally, the suppression and misdirection of the seeking circuitry – especially with actions that are inconsistent with our highest values – when combined with the absence of satisfaction, can cause or greatly worsen a sense of demoralization. When we feel too depressed and defeated to live up to our highest values and be our best selves, and when we’re only escaping our depression by doing things that we feel ashamed of, it can be terribly demoralizing.

Of course, sometimes people can be fearful or anxious and depressed at the same time. And we may seek to avoid and escape from other unwanted experiences too, for example feeling emotionally numb or disconnected from other people and life.

So long as our seeking circuitry is suppressed or is focused almost entirely on avoiding and escaping suffering – rather than on seeking what is truly satisfying and fulfilling – we are caught in cycles of suffering.

Cycles of Healing and Happiness

Just as there are fundamental cycles of suffering, there are fundamental cycles of healing and happiness.

A key contribution of the framework offered here is its focus on the seeking circuitry, including not just its potential roles in suffering but also in healing and finding genuine happiness and fulfillment in life.

Two keys to healing and recovery – and to moral and spiritual transformation – are focusing one’s seeking circuitry on pursuing things that are (1) genuinely healing, not merely brief escapes from suffering, and (2) truly satisfying and fulfilling, not merely fleeting or unhealthy pleasures.

That’s why there are two fundamental cycles of healing and happiness: seeking to engage and transform suffering, and seeking true goods.

While each of these cycles supports the other and they can overlap, it’s helpful to consider them separately – particularly with respect to how each can change the activities of the circuitries of seeking, fear, satisfaction, and embodiment, as well as the relationships among them.

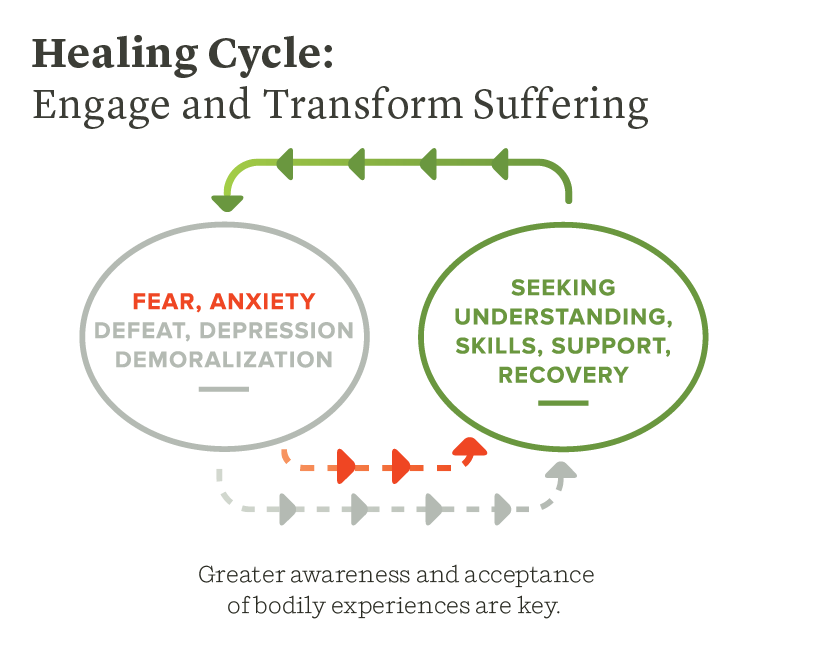

Healing Cycle: Seeking to Engage and Transform Suffering

This brain-based healing cycle is about seeking to know, tolerate, understand, and make positive use of pain and suffering.

What it means to seek to engage and transform suffering can be similar or different for different people. For some, seeking to know and understand their suffering means working with a therapist or counselor. Others seek to engage with and transform their suffering by talking with family and friends. Some seek such understanding and support from members of their religious or spiritual community, or a support group for people dealing with the same problems and struggles. Some write about their experiences of suffering, or express them through art.

For more and more people, as discussed below, this healing cycle involves engaging in meditation or other contemplative practices that cultivate mindful and loving experiences of embodiment, and mindful and loving thoughts and actions.

Seeking to engage, safely, with suffering in one’s body

Whatever works for a particular person, the seeking to engage and transform suffering healing cycle entails just that: seeking to engagewith pain, suffering and unwanted experiences, and doing so in healthy and healing ways that break cycles of suffering.

For example, someone may seek to experience feelings of shame associated with a sexual abuse experience, in order to better understand where those feelings come from and to render them more manageable. But this will only be healing if they first (with someone else’s help) accesses feelings of safety in their body and compassion toward themself.

Or someone may seek to understand the roots of his addictive behavior, and seek help to learn new skills for dealing with unwanted feelings that he has been trying to escape with alcohol, drugs, sex, or constant work.

However we engage in this cycle, it is critical that the process actively involves the embodiment circuitry, which registers and allows awareness of our suffering. It is difficult, if not impossible, for us to know, understand or transform our suffering without experiencing how it feels in our bodies.

For some people, especially traumatized people, attending to bodily aspects of suffering can be very difficult and triggering. They will need extra patience and support, and probably some specifically body-focused approaches (e.g., trauma-sensitive yoga).

For everyone this healing cycle requires strong motivation, because it can be quite unpleasant to engage with our suffering, which we typically attempt to avoid and escape.

To sustain that seeking to engage with our suffering, and to find success in doing so, we need support. For many of us that support will come mostly from a therapist or counselor; religious or spiritual teachers can be extremely helpful too.

Indeed, as shown in the image depicting this healing cycle (below), it can involve seeking a variety of resources that enable engagement with suffering and its transformation. These may include not only healing-promoting support from others, but learning new skills for regulating our emotions and thoughts. Other necessary resources may include knowledge of and insights into human suffering and healing, in general and in ourselves as unique individuals; healing attitudes, including compassion and kindness toward our suffering; and cultivating new habits that help us engage with and transform suffering, to replace old habits that only exacerbate it. (Many of these capacities depend on the brain’s executive circuitry; see Key Brain Circuitries.)

In this cycle there is still suffering, but rather than seeking escape from suffering, seeking is focused on acquiring resources that allow engaging with suffering (especially as bodily experiences processed by the embodiment circuitry) in constructive and healthy ways that transform suffering experiences into vehicles of recovery and healing (even redemption). The seeking circuitry is no longer driven by fear of suffering, but instead by motivations to know, understand, heal and transform one’s suffering.

Yes, engaging in this healing cycle is difficult. Sometimes it’s painful. But the payoff is huge. We can come to live in much less fear, and with much less aversion to the inevitable unwanted experiences life sends our way. We can have more compassion for ourselves, no matter what we’re going through. We can find courage and strength inside that we never realized were there.

And as addressed next, we can free up our brain’s seeking circuitry to pursue much more satisfying and fulfilling things in life, which will bring greater happiness and health than we ever imagined possible.

Healing and Happiness Cycle: Seeking True Goods

Fortunately, healing isn’t all about seeking to deal more effectively with pain and suffering. If that’s all we ever focus on – or all the people we’ve enlisted to help us focus on – the work of healing is not so appealing or inspiring for anyone involved.

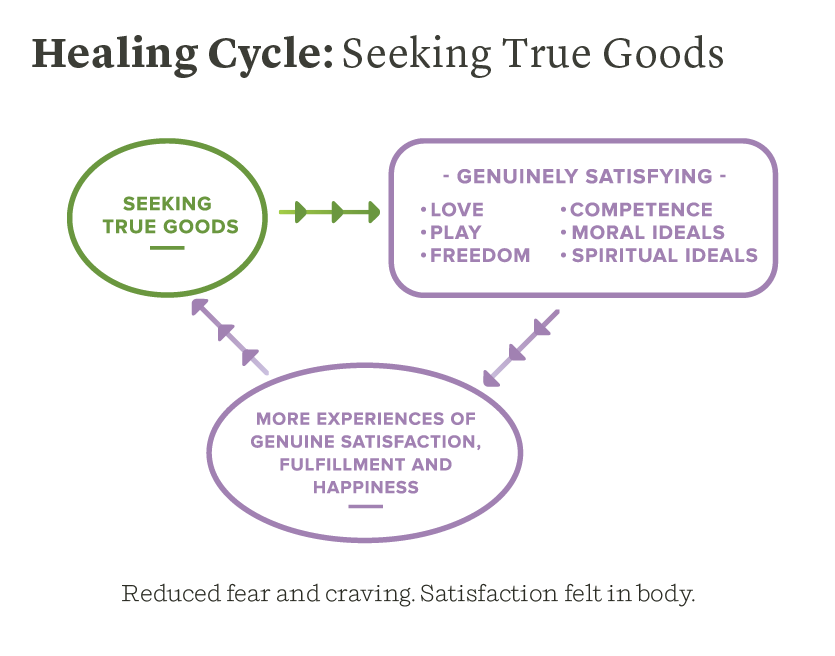

In the second fundamental healing cycle, seeking true goods, we are harnessing our brain’s seeking circuitry – that always-active and powerful driver of our thoughts and behaviors – to seeking out the truly ‘good things in life.’

These true goods include love, playfulness, and joy. In this healing cycle one seeks and experiences the kind of happiness and satisfaction that come from being a good friend, a good spouse or partner, a good parent, good at our job or a genuine contributor to our community.

Seeking and embodying the truly ‘good things in life’

We all need to sort out, for ourselves, what truly makes us happy; what we find to be the greatest goods in life, the things we most deeply value and find most satisfying to experience.

This process of exploration and discovery may take some time, especially if we’ve had little experience with true goods and genuine happiness. It usually requires the support of others who do not judge our values or push us to adopt theirs, but instead give us the space, as well as the support and inspiration, to sort things out for ourselves – and to awaken and harness our seeking circuitry to this pursuit.

A therapy that many find helpful with this is Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, or ACT, which has a major focus on helping people sort through their values and goals, and then commit to behaving consistently with the values that are most important to them. Another is motivational interviewing, which has helped many people overcome addictions and make other changes that bring their lives into harmony with their deepest values.

Sometimes, however, people have very powerful insights or epiphanies that they were not expecting or seeking, but happen suddenly and transform them permanently. William Miller, a great addiction researcher and developer of motivational interviewing, and his colleague Janet C’de Baca wrote about such sudden and permanent transformations in their book Quantum Change. Common to such experiences, as they document with individual stories and statistical analyses, are fundamental reorganizations of one’s identity and values. What is valued, and therefore what one seeks, is completely reorganized: universally recognized true goods move to the top and stay there. In short, one suddenly and permanently enters into a very deep and powerful seeking true goods healing and happiness cycle.

As shown in the image below, the seeking true goods cycle involves aligning the seeking circuitry with one’s deepest needs and longings.

A person engaging in this healing and happiness cycle is seeking what will be genuinely satisfying and fulfilling, and spending more and more time experiencing that satisfaction and fulfillment.

Also, the more we activate our brain’s satisfaction circuitry as a result of successful seeking of this kind, and the more we occupy our embodiment circuitry with the sensations of that satisfaction, the less power the circuitries of fear and seeking have over us. That’s what it means to be satisfied and content: accepting and embracing this moment, without wanting or seeking more from it; accepting whatever may come next, without fear.

To summarize, in the seeking true good cycle the seeking circuitry is focused on wanting and pursuing what is genuinely satisfying and fulfilling. This leads to more experiences of genuine satisfaction, fulfillment and happiness, including the bodily aspects of such experiences as registered by the embodiment circuitry. This in turn increases motivation to seek and enjoy more true goods (rather than quick fixes and other ‘false goods’ that perpetuate suffering), which decreases fear circuitry activation and suffering in general.

Contemplative Practices for Seeking to Engage and Transform Suffering

Contemplative practices can be used to carefully attend to and investigate any experience that human beings may have – including those of pain and suffering, and satisfaction and happiness – and to cultivate capacities for doing so.

Employing our capacities for attention and investigation in this way are central to the seeking to engage and transform suffering healing cycle, which involves seeking to know, tolerate, understand, and make positive use of our pain and suffering.

Readiness and Preparation

Before directly facing pain and suffering, we need skills for managing our painful and unwanted feelings and body sensations, which may include traumatic memories and addictive cravings. For example, therapists competent at working with traumatized people, including those with addictions, understand that the first stage of recovery is focused on learning and strengthening self-care and self-regulation skills.

For those struggling with extreme psychological suffering (perhaps partly due to trauma), there is another prerequisite for safely facing the pain and suffering: a relationship with someone, often a therapist, who is not only competent at guiding them through the stages of recovery, but truly understands and cares for them.

Mindfulness

A common definition of mindfulness is “the awareness that emerges through paying attention on purpose, in the present moment, and nonjudgmentally to the unfolding of experience moment by moment” (Kabat-Zinn, 2003).

Mindfulness can be an excellent tool for exploring extremes of suffering, including trauma-related memories, feelings, bodily experiences, thought processes and ways of relating to others. Experiences that had previously felt too unbearable to focus on can be explored and investigated, and seen as passing sensations and thoughts that arise under particular conditions, without resorting to seeking escape. When habitual reactions arise, or suffering cycles begin to unfold, one can mindfully observe and even experientially understand them, and not get carried away.

Bodily awareness is key

Mindful awareness of bodily sensations, that is, one’s moment-to-moment experiences of embodiment, is the foundation for attending to and exploring one’s emotions, thoughts, behaviors and relationship patterns.

Only with that grounding in embodied awareness – of the impermanent bodily sensations – can we effectively bring mindful awareness to emotions and thoughts; otherwise we are repeatedly swept away in habitual cycles of seeking brief escapes and quick-fixes that perpetuate suffering and disconnection from present experience.

Mindfulness can enable direct and safe engagement with the bodily sensations of pain and suffering, which enables us to experience and understand those sensations as just that: passing sensory information that does not constitute a major threat that must be escaped or defended against. Rather than seeking to control or escape those sensations, which brings no healing but does perpetuate suffering, mindfulness allows tolerance and compassionate understanding of those sensations, and other constructive and healing responses to them.

In short, mindfulness of bodily sensations plays a central role in the transformation of suffering experiences into opportunities for healing, even spiritual awakening.

Here I want to note that, especially for very traumatized people, attending to body sensations associated with trauma, even unintentionally in the midst of a mindfulness exercise, can be quite triggering (e.g., of traumatic memories and trauma-based emotional reactions) and overwhelming. So it can be safest – and most helpful – to first experience mindfulness in the context of a relationship with a mindful therapist. This is illustrated by several case vignettes in chapters (e.g., by Tara Brach and by Pat Ogden) of a book I co-edited.

Certainly mindfulness and other contemplative methods for engaging with and transforming suffering are not quick fixes or panaceas. Even after cultivating the self-care and self-regulation skills needed to engage directly with trauma or other forms of extreme suffering, engaging with and transforming suffering can be a long process. (However, sometimes healing can be sudden and lasting, as documented by Miller and C’de Baca in Quantum Change, although it is unrealistic to expect or count on such experiences.)

Also, we are all creatures of habit, and old habits can be hard to break, especially if they (have seemed to) ensure our physical or psychological survival. But with a foundation of self-regulation skills, regular practice, and relationships that support both, mindfully engaging with one’s suffering can facilitate the healing cycle of seeking to engage and transform suffering.

In my chapter, Harnessing the Seeking, Satisfaction and Embodiment Circuitries in Contemplative Approaches to Healing Trauma, and in several other chapters of Mindfulness-Oriented Interventions for Trauma (co-edited with colleagues), there are many examples of how mindfulness can play an integral role in the healing cycle of seeking to engage and transform suffering.

Contemplative Practices and Seeking True Goods

Seeking true goods, the second healing cycle of the framework I am sharing, includes the use of contemplative practices to harness the brain’s seeking circuitry, which when wrongly directed causes so much of our suffering, to the pursuit of true goods that bring genuine happiness.

Our seeking circuitry is always active. Fortunately, unlike many other aspects of brain function, our seeking circuitry is accessible to us. Its functioning is something we can bring into awareness and contemplate.

And we can choose: What shall I seek? What should I seek as my highest priorities? What do I want to seek in this relationship? In this moment? In this moment with its conflicting motivations, in which very different parts of me are wanting to respond in very different ways?

We can also contemplate and choose our answers to these questions: What really makes me happy? What is my motivation for doing (or thinking or saying or writing) this?

These questions and choices are at the heart of contemplative practices and how we put them into practice in our lives.

What should we seek? Religious and spiritual leaders have long sought (whether wisely or in confusion themselves) to help people seek transcendent ‘true goods’ – obedience to God’s law, surrender to God’s will; an intimate relationship with God or Jesus; loving others, even our ‘enemies,’ as we love ourselves; forever striving to free all beings from suffering.

Profit-seeking companies, advertisers and politicians bombard us with sights, sounds and words designed to harness our seeking circuitry to the (perceived) benefits they seek for themselves. The Declaration of Independence of the United States declares it to be a ‘self-evident’ truth that we are endowed by our creator with unalienable rights, not only to life and liberty, but ‘the pursuit of happiness.’

In short, the brain’s seeking circuitry is central to human existence.

Yet around the world – not only in popular cultures but within neuroscience, psychology and psychiatry – the seeking circuitry has been largely unknown, unappreciated, and misunderstood.

So far, aside from addiction research, the brain’s seeking circuitry has been largely unrecognized and overlooked. (And among addiction researchers, there remains confusion about the ‘reward circuitry,’ of which the seeking circuitry is a key but often inadequately understood component.) Similarly, the recent focus on mindfulness and other contemplative methods in psychology has involved little consideration of the seeking circuitry. (There are good reasons for this, including lack of knowledge of this critical aspect of brain function; a focus, shared with medicine, on treating illness and reducing suffering rather than promoting health and happiness; and fears of venturing into realms of morality, religion and spirituality.)

Indeed, discussions of mindfulness often include cautions about the danger of seeking any result, and the concern that doing so is incompatible with mindfulness. Certainly seeking results can be an obstacle to mindfulness and the unsought and unexpected insights and transformations that it can bring. But as stated in the ‘Second Noble Truth’ of Buddhism, the problem is craving conditioned by ignorance – not seeking itself, which need not involve craving and is inseparable from normative brain function, healthy living, and embodied life itself.

Furthermore, as Purser and Loy (2013) have observed, “Buddhists differentiate between Right Mindfulness (samma sati) and Wrong Mindfulness (miccha sati),” and this distinction addresses “whether the quality of awareness is characterized by wholesome intentions and positive mental qualities that lead to human flourishing and optimal well-being for others as well as oneself.” In short, Right Mindfulness entails seeking true goods for oneself and others (not just nonjudgmental awareness of present experience and any benefits that brings, although those are considerable).

The meditation teacher and therapist Tara Brach has movingly written of an experience when, after days of having grasped, resisted and attempted to control feelings of longing for love, she recognized the reality that seeking is central to life itself:

“Late one evening I sat meditating alone in my room. My attention moved deeper and deeper into longing, until I felt as if I might explode with its heartbreaking urgency. Yet at the same time I knew that was exactly what I wanted – I wanted to die into longing, into communion, into love itself. At that moment I could finally let my longing be all that it was. I even invited it…” (Brach, 2003, pp.153-154).

Similarly, in an interview, the widely respected Buddhist teacher, author, and peace activist Thich Nhat Hanh recalled this formative experience when he was seven or eight years old:

“One day I saw a picture of the Buddha… [H]e was sitting on the grass very peaceful, smiling, and I was impressed. Around me people were not like that, so I had the desire to be someone like him. And I nourished that kind of desire until the age of 16, when I had the permission from my parents to go and ordain as a Buddhist monk…. We call it the beginner’s mind: The deep intention, the deepest desire that one person may have. And I can say that since that time, until this day, this beginner’s mind is still alive in me” (interview with Oprah Winfrey, 2012, emphasis in spoken words).

Yes, seeking can cause problems – when it becomes craving, grasping, clinging and attachment to passing things that cannot bring genuine happiness. But seeking can be focused on true goods that, when experienced but not clung to, bring genuine happiness and reduce craving and attachment.

While ‘mindfulness’ and Buddhism have recently become popular, even trendy, sages of the great philosophical and religious traditions of the West have always recognized the centrality of seeking in human life – and that where we focus our seeking is the key to happiness and goodness. Those Western traditions, including Christianity, have always had spiritual teachers who understood that harnessing one’s seeking to the pursuit of true goods is a key, perhaps the key, to spiritual transformation and ‘the good life.’

Great philosophers like Plato and Aristotle wrote a lot about what is truly good, what is truly worth seeking and embodying, and the nature of the good life.

In Boethius’ 6th century masterpiece, The Consolation of Philosophy, one of the most influential books ever written in the (Christian) West, he repeatedly pointed out that nothing is more important than discovering and seeking what is truly good. He observed, “A desire for true good is planted by nature in human minds. Only error leads them astray towards false goods.” He wrote, “In spite of a clouded memory, the mind seeks its own good, though like a drunkard it cannot find the path home.”

Boethius also observed that “Each person considers what he desires above all else to be the supreme good.” The great Roman poet Virgil pointed to the same truth, which can be uncomfortable for us to acknowledge, “Every person makes a god of his own desire.”

We can ask ourselves: What do I really want? What do I really seek? What do I really long to have, and to be? What do I really believe are the greatest goods?

In our day to day lives, actions speak louder than words. Only by honestly investigating and acknowledging what we are actually seeking – day by day, moment by moment, thought by thought, action by action – and by harnessing our seeking circuitry to the pursuit of what is truly good – thus truly fulfilling – can we live with integrity and cultivate genuine happiness.

We all know this in our hearts, but of course it’s easier said than done. And we can’t do it alone. We need the support of others. Most of us need the support of philosophical, religious and/or spiritual traditions. And we need disciplined practices for cultivating genuine insight into our motivations, and disciplined practices for harnessing our seeking circuitry to the pursuit of true goods.

Seeking Kindness, Compassion, and Love

For Thich Nhat Hanh it was an image of a happy and loving Buddha; for many Christians, it’s an image of Jesus. Every religion and spiritual tradition has its images of wise, loving and happy beings that can powerfully activate our seeking circuitry and deepest longings.

Yet often more effective for cultivating love within ourselves – at least initially – are simpler and more common images that are easily called to mind or found on the internet, like a cute baby, a puppy, a kitten. The key to successfully utilizing images in this way: bringing the image to mind causes motivations and feelings of kindness, compassion, and love to arise spontaneously and effortlessly.

In the metta practice of the Theravadin Buddhist tradition, now being taught to many people around the world, including by therapists and counselors, the focusing of attention on such an image, and the bodily sensations of spontaneously arising motivations and feelings, is combined with internally repeating phrases like these:

May you be happy.

May you be healthy.

May you be at peace.

May you be free of suffering.

In this way, during this practice visual imagination and verbal thoughts (which are typically absorbed in memories, plans, and fantasies of imagined rewards), along with attention to bodily sensations, are used to harness the brain’s seeking circuitry to kindness, compassion, and love.

Harnessing the brain’s seeking circuitry to cultivating embodied and satisfying kindness, compassion, and love.

If while doing this practice we experience in our bodies feelings of kindness, compassion and love, we occupy the embodiment circuitry with them.

If those good feelings are accompanied by feelings of contentment, peace, satisfaction and joy, then this practice also involves the satisfaction circuitry.

And to the extent we experience the bodily sensations of contentment, peace and satisfaction, the embodiment and satisfaction circuitries are not only involved, but being transformed.

In the understanding I am sharing here, harnessing the seeking, satisfaction and embodiment circuitries to the cultivation of kindness, compassion, and love is the most basic and powerful form of the seeking true goods healing cycle.

The benefits of cultivating kindness, compassion and love toward ourselves and others are many – especially for those of us who are suffering greatly and have thus far experienced little of these true goods in our lives.

As with mindfulness, however, things can be more complex. Given the neglect, losses, abuses and betrayals that many people have experienced in their lives, feelings of kindness, compassion and love can trigger fear. This is normal, and there are many ways that people can be helped to gently and safely explore, understand and overcome these obstacles to receiving, cultivating and giving kindness, compassion and love.

Other ‘True Goods’

There is a good case, made by many for millennia, that love – which we can experience and express in many ways – is the greatest good and the greatest source of genuine human happiness.

But most of us agree there are other (if lesser) ‘true goods’ too. Other experiences and goals that are most worthy of seeking and most likely to bring genuine happiness.

Depending on our personality, our cultural and religious background and several other factors, we may highly value and seek various things along a continuum from false to true goods (e.g., power, money, technology toys, entertainment, sexual stimulation, physical health, beauty, creativity, knowledge, courage, generosity, connection with nature, playfulness, achievement, contributing to others through our work).

The world’s religious and spiritual traditions supremely value wisdom, which includes liberation from ignorance and, to use a central Buddhist conception, ‘seeing things as they really are’ – not as we fear or want them to be.

Such wisdom entails accurately perceiving and knowing oneself, per the ancient Delphic maxim.

Combining mindfulness practice with analytic meditation involving self-questioning – and the courage to know ourselves – can yield insights into our true motivations for what we do and say. Some therapies help cultivate this kind of insight too. When we do this, we find that even our efforts to pursue true goods are sometimes largely motivated by fears of failure, judgment or rejection; by cravings for lesser goods like others’ attention or admiration; even by false goods like competitive advantage or revenge.

Seeking the true good of self-knowledge can help us to mindfully and compassionately acknowledge such normal human short-comings, to gain more freedom from them, and to focus our seeking on true goods and genuine happiness.

In short, there are many contemplative practices – especially but not only those for cultivating kindness, compassion and love – that can bring healing from suffering, and much more, by harnessing the brains’ seeking circuitry to the pursuit of true goods and genuine happiness.

Summary and Conclusions

On this webpage I am offering a framework for understanding key brain and psychological processes involved in suffering, healing and happiness – particularly healing and happiness fostered by contemplative practices for cultivating mindfulness, kindness, compassion and love.

I have drawn on scientific, clinical and contemplative knowledge to provide an integrative vision. And while simplifying things in some ways, this framework acknowledges the complexity of human suffering and healing. Also, respected neuroscience colleagues asked to review my writing on this framework (for my book chapter) found nothing inconsistent with current scientific knowledge, although it is important to note that direct research on interactions between the brain circuitries of fear, seeking, satisfaction and embodiment is currently limited (but substantive and growing).

Certainly more research is needed. In the meantime, those of us seeking healing and genuine happiness for ourselves and others can better appreciate and explore the power of contemplative practices – Eastern and Western, secular and religious – to harness our brains’ seeking, satisfaction, embodiment and other key circuitries to decrease suffering and to cultivate more mindful, loving and happy minds, bodies, relationships, families and communities.

Exercises and Handouts

Here are some exercises and handouts that foster greater experiential understanding of the key brain circuitries and fundamental cycles of suffering, healing and happiness.

What I Do with My Seeking Circuitry – One-page handout to promote reflection and possibly new action. This handout is used in two of the exercises in the handout below.

Individual and Partner Exercises – I lead people through these exercises during my trainings on harnessing key brain circuitries for healing and happiness, especially longer trainings where we have lots of time to engage in contemplative practices and exercises.

Additional Notes

While I have deep respect for Western philosophical, religious and spiritual traditions, and these have many positive influences on my thinking and life, Buddhist psychology and meditation practice are key sources of the framework presented here. Particularly influential are the focuses of Buddhist psychology and meditation on fear/aversion and craving, which, along with ignorance, are known in Buddhist psychology as the ‘three poisons’ or three root causes of suffering.

As meditation masters teach, an essential precondition of mindfulness is the concentration that arises from the practice of concentration meditation. Without a foundation of concentration, mindfulness is impossible because attention is swept away by thoughts, emotions, and images that revolve around fears and wants – that is, are driven by the circuitries of fear and seeking.

Importantly, the achievement of meditative concentration requires both (1) quieting the fear circuitry and (2) adjusting activity of the seeking circuitry to the optimal amount required to sustain meditative focus (neither too little nor too much intensity of seeking). This is indicated by the Tibetan term for the concentration practice of shamatha, which means ‘calm abiding’ (Wallace, 1998).

Similarly, in the Buddhist tradition mindfulness itself is a precondition for something more transformative than the present-focused awareness, stress-reduction and other benefits for which it is now promoted. That is, mindfulness can be a foundation for liberating insight, or vipassana, which includes directly observing how aversion, seeking, and habitual relationships between them – which can otherwise unfold outside of awareness, in just fractions of a second – are causing suffering for oneself and others.

Buddhist psychology and meditation practice, along with Western contemplative traditions, are also sources of my focus on harnessing the brain’s seeking circuitry to the pursuit of what is truly good and satisfying. In Mahayana Buddhism, the greatest motivation, said to be an expression of bodhicitta or ‘mind of enlightenment,’ is the loving and compassionate motivation to seek enlightenment for the benefit of all beings, so that one can help all beings to achieve liberation from suffering and genuine happiness.

Finally, according to Vajrayana or tantric Buddhism (the Dalai Lama’s tradition), as explained in the classic Introduction to Tantra: The Transformation of Desire, “it is only through the skillful use of desirous energy [in biological terms, the seeking circuitry] and by building up the habit of experiencing what we might call true pleasure [in biological terms, strongly activating the satisfaction circuitry] that we can hope to achieve the everlasting bliss and joy of full illumination” (Yeshe, 2001, p.10).